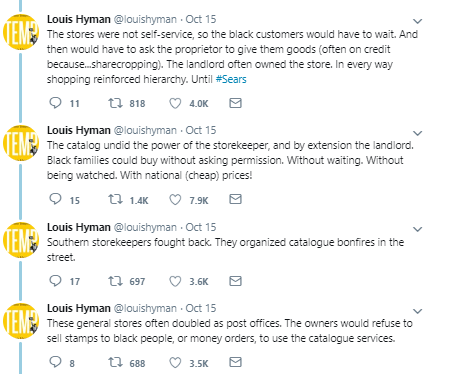

The thread argues that Sears catalogs helped to undermine

Jim Crow. To preserve racial control, Southern store owners tried to

keep African Americans in the South from using Sears, but Sears responded to

this opposition. Sears not only acted to undermine Jim Crow it

did so intentionally.

Scott Cunnigham raised an interesting question to economic historians on twitter about how one might try to estimate the effect of the Sears catalog. So far as I know, no one has yet done that, but Elizabeth Ruth Perlman and Steven Sprick Schuster may be taking a stab at it (see here).

In addition, to the quantitative significance of the catalog, I wondered what sources the story was based upon. The story seems plausible, but what evidence is it based on? Like most people, Hyman doesn’t provide references for his tweets. The video also does not state the sources for the story, and it did not appear to be included in the American Capitalism Reader that he and Baptist put together. I tweeted a reply asking him about it, but it must have been one of the thousands of responses to the thread.

Scott Cunnigham raised an interesting question to economic historians on twitter about how one might try to estimate the effect of the Sears catalog. So far as I know, no one has yet done that, but Elizabeth Ruth Perlman and Steven Sprick Schuster may be taking a stab at it (see here).

In addition, to the quantitative significance of the catalog, I wondered what sources the story was based upon. The story seems plausible, but what evidence is it based on? Like most people, Hyman doesn’t provide references for his tweets. The video also does not state the sources for the story, and it did not appear to be included in the American Capitalism Reader that he and Baptist put together. I tweeted a reply asking him about it, but it must have been one of the thousands of responses to the thread.

Although I do not know for certain what source or sources Hyman used, Grace Elizabeth Hale told a similar in her Making

Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South, 1890-1940 (1999). Here

are excerpts from pages and of Making

Whiteness.

The story is essentially the same. There is, however one noticeable difference between the

two stories in Hale’s version, even though she is writing a book about race, she says that store owners refuse to sell to people who had not paid their accounts. In Hyman's

version store owners refuse to sell to people because they are black. In the first,

store owners are opposing a competitor regardless of who the customer is. In

the second, the refusal is based on race. It is suggested, based upon the statement from the catalog about giving letters and money to the mail carrier, that Sears responded to these actions by the store owners. But the full quote from the catalog was "IF YOU LIVE ON A RURAL MAIL ROUTE, just give the letter and the money to the mail carrier.." The all caps is in the original. The instructions were repeated in Swedish and German.

Not only is the story in Hyman and Hale the same, much of the wording is the same. Both contain the quotes: "just give the letter and the money to the mail carrier and he will get the money order at the post office and mail it in the letter for you" and “these fellows could not afford to show their faces as retailers.” It seems reasonable to infer that either Hale was Hyman's primary source or they both drew from the same sources.

Hale sources are provided in two footnotes.

The first footnote is for the statements that rural storekeepers refused to sell stamps or money orders to some customers who owed on their accounts and the statement from the Sears Catalog about giving the money to your mail carrier. Thomas Clark states that : "Sometimes a customer was brought under control by the merchants refusal to order goods until he had paid his bill (page 73)." Clark was a prominent historian, but his The Southern Country Store does not provide citations. The other sources in that footnote refer to the catalog statement about giving money to the mail carrier. It is not clear, however, that Sears was trying to counter the actions of store owners rather than simply informing rural residents throughout the country that they could take advantage of rural free delivery and did not actually have to make a trip to the post office.

The other footnote cites three sources in support of the statements about rumors that Sears was black and the burning of catalogs: Stuart Ewen and Elizabeth Ewen Channels of Desire: Mass Images and the Shaping of American Consciousness published in 1982, Robert Hendrickson The Grand Emporiums: The Illustrated History of America’s Great Department Stores published in 1979, and Gordon L. Weil Sears Roebuck USA: The Great American Catalog Store and How it Grew published in 1977.

The first footnote is for the statements that rural storekeepers refused to sell stamps or money orders to some customers who owed on their accounts and the statement from the Sears Catalog about giving the money to your mail carrier. Thomas Clark states that : "Sometimes a customer was brought under control by the merchants refusal to order goods until he had paid his bill (page 73)." Clark was a prominent historian, but his The Southern Country Store does not provide citations. The other sources in that footnote refer to the catalog statement about giving money to the mail carrier. It is not clear, however, that Sears was trying to counter the actions of store owners rather than simply informing rural residents throughout the country that they could take advantage of rural free delivery and did not actually have to make a trip to the post office.

The other footnote cites three sources in support of the statements about rumors that Sears was black and the burning of catalogs: Stuart Ewen and Elizabeth Ewen Channels of Desire: Mass Images and the Shaping of American Consciousness published in 1982, Robert Hendrickson The Grand Emporiums: The Illustrated History of America’s Great Department Stores published in 1979, and Gordon L. Weil Sears Roebuck USA: The Great American Catalog Store and How it Grew published in 1977.

Ewen and Ewen say pretty much the same thing that Hale and

Hyman did

Ewen and Ewen do not mention the refusal to sell stamps and

money orders, but they do have the stories about rumors that Sears and

Montgomery Ward were black, including the quote about "these fellows." They also do not cite

Hendrickson and Weil.

Hendrickson also tells of rumors about race and catalog burning, but does not mention refusals to sell stamps or money orders:

Weil also describes the opposition of small retailers and their use of racial rumors.

So far the trail of citations has led us to Weil, who largely says

the same things that Ewen and Ewen did, but we can see that the quote about "these fellows" not showing their faces isn't actually evidence; it was just Weil’s interpretation.

What sources did Hendrickson and Weil base their interpretations on? Good

question. Neither Hendrickson or Weil is an academic history. There are no notes or references. Weil does, however, mention in his introduction that Catalogues and Counters: A History of Sears Roebuck and Company by Boris Emmet and John E. Jeuck was useful. (Seeing it listed on Amazon for $246 makes me feel fortunate to have picked up a copy at the library book sale for $2).

Emmet and Jeuck also tell the stories about rumors that Sears and Roebuck were black, and the story about small town merchants burning catalogs. Emmet and Jeuck were academics and their massive volume is heavily footnoted. The footnote in regard to the rumors about Sears and Roebuck being black cites an unpublished manuscript on the company's history written by Alvah Roebuck, suggesting that he remembered hearing such rumors as late as the 1930s. The footnotes about catalog burning and other opposition from small town merchants cites page 105 of Asher and Heal Send No Money Asher was a former Sears executive. Like the books by Weil and Hendrickson it does not cite sources. Page 105 does state that "George Milburn, in his book entitled "Catalogue," reveals the whole history of the home dealer's campaign against the mail order houses." George Milburn's Catalogue was a satirical novel about the the effects of the wish book on a small Oklahoma town.

I believe that I have now arrived at the end of the line. The claim about store owners refusing to sell stamps or money orders to blacks does not seem to appear in the previous literature. The claim that store owners refused to provide services to people whose accounts were not up to date appears to rest on Clark's statement in The Southern Country Store, which he does not provide any sources to support. Sears definitely told people they could give their money directly to postal carriers, but I did not find any evidence that they did this because of opposition from country store owners as opposed to just trying to make things easier for their customers. The claim about rumors that Sears and Roebuck were black appears to ultimately rest on the recollection of Roebuck in an unpublished manuscript. I wasn't able to trace the rumor about Ward past Weil and Hendrickson. The claims about catalog burning appear to be based on a novel.

The bottom line of all this is that we know very little about the impact of Sears in the South or other rural areas, and consequently we no little about its ability to undermine some of the results of Jim Crow. It is quite plausible that Sears provided large benefits like those suggested by Hyman, but we don’t know. It is possible that store owners spread rumors about race, but we have only Roebuck's recollection to that effect. It is possible that they organized catalog burnings, but we do not know. It is possible that some of Sears actions were attempts to counter racism, but we don’t know.

The bottom line of all this is that we know very little about the impact of Sears in the South or other rural areas, and consequently we no little about its ability to undermine some of the results of Jim Crow. It is quite plausible that Sears provided large benefits like those suggested by Hyman, but we don’t know. It is possible that store owners spread rumors about race, but we have only Roebuck's recollection to that effect. It is possible that they organized catalog burnings, but we do not know. It is possible that some of Sears actions were attempts to counter racism, but we don’t know.

Hyman’s tweet thread shouldn’t serve as a call to debate

whether or not Sears was an example of the positive aspects of capitalism. It should

be a call to historians to go out and actually find out what Sears did.