“You think it’s dead but de past ain’t

stopped breathin’ yet.” Zora Neale Hurston, 1934.

The past is obviously central to discussions of reparations for slavery. At the hearing on a commission to study reparations

Ta-Nehisi

Coates cites Ed Baptist’s The Half Has Never Been Told, claiming

that 60 percent of GDP was accounted for by slave produced cotton and that the

value of slaves was greater than all other assets combined. Both statements are

incorrect. Baptist (and the historians who have not called him out on the errors

in his book) can be blamed for the first error but not for the second.

Coates is wrong about the percentage

of GDP accounted for by slave labor because Baptist is wrong.

The following section in bold is from

an earlier blog post of mine.

Baptist The Half has Never

Been Told (page 321-2)

“But here’s a back- of- the –envelope

accounting of cotton’s role in the US economy in the era of slavery expansion.

In 1836, the total amount of economic activity―the value of all the goods and

services produced―in the United States was about $1.5 billion. Of this, the

value of the cotton crop itself, total pounds multiplied by average price per

pound―$77 million―was about 5 percent of that entire gross domestic product.

This percentage might seem small, but after subsistence agriculture, cotton

sales were the largest single source of value in the American economy. Even

this number, however, barely begins to measure the goods and services directly

generated by cotton production. The freight of cotton to Liverpool by sea,

insurance and interest paid on commercial credit―all would bring the total to

more than $100 million (see Table 4.1).

Next

come the second- order effects that comprised the goods and services necessary

to produce cotton. There was the purchase of slaves―perhaps $40 million in 1836

alone, a year that made many memories of long marches forced on stolen people.

Then there was the purchase of land, the cost of credit for such purchases, the

pork and the corn bought at the river landings, the axes that the slaves used

to clear land and the cloth they wore, even the luxury goods and other spending

by the slaveholding families. All of that probably added up to about $100

million more.

Third

order effects, the hardest to calculate, included the money spent by millworkers

and Illinois hog farmers, the wages paid to steamboat workers, and the revenues

yielded by investments made with the profits of the merchants, manufacturers,

and slave traders who derived some or all of their income either directly or

indirectly from the southwestern fields. These third order effects would also

include the dollars spent and spent again in communities where cotton related

trades made a significant impact another category of these effects is the value

of foreign goods imported on credit sustained the opposite flow of

cotton. All these goods and services might have added up to $200 million. Given

the short term of most commercial credit in 1836, each dollar “imported” for

cotton would be turned over about twice a year: $400 million. All told more

than $600 million, or almost half of the economic activity in the United States

in 1836, derived directly or indirectly from cotton produced by the million odd

slaves― 6 percent of the total US population―who in that year toiled in labor

camps on slavery’s frontier.”

Where do I begin? The approach is

fundamentally flawed. Baptist begins with gross domestic product (GDP), the

value of all the final goods and services produced in the country during the

year. He refers to this as a measure of the total economic activity. He notes

that the value of cotton production equaled about 5 % percent of GDP. No

problems so far. But he then adds the cost of the inputs to the production of

cotton. Anyone who has taken Principles of Macroeconomics knows that you can’t

do this; it is referred to as double counting. If I buy $1000 worth of wood and

then make it into a table that I sell for $1,500, we do not add $1,000 and

$1,500 because the value of the wood is included in the value of the table, the

final good. If he is going to engage in double counting for cotton he would

need to engage in double counting for all other goods. He then adds the costs

of transportation and insurance; these only count toward US GDP to the extent

that they are produced by Americans. He also adds the sales of assets: land and

slaves. Again, the sales of assets are not counted in GDP. GDP only counts the

value of final goods and services produced during the year. Not all purchases

are counted as part of GDP. Only purchases of newly produced goods and services

are counted in GDP. Comparing his calculation of economic activity

related to cotton to GDP is meaningless.

There is, however, an even deeper

problem with this back of the envelope accounting:

perhaps $40 million

probably added up to about $100

million

might have added up to $200

million

Baptist is simply pulling numbers out

of thin air, or a hat, or wherever it is that he gets them. Back of the

envelope calculations tend to involve simplifying assumptions. Baptist seems to

understand the term to mean that he can just make things up. The only reference

provided is to Table 4.1. Table 4.1 does not provide, as one might assume,

information about shipping and insurance. It does not even have any information

at all for the year 1836.

Both historians and authors of

fiction tell stories, but the stories that historians tell are distinguished

from fiction by their grounding in the sources. Historians are constrained to

tell stories that they can support with evidence from their sources. Baptist

has thrown off this constraint and set himself free to simply make up numbers

(or events).

Coates is also wrong about the relative

importance of wealth in slaves, but he has to take the blame for this one

himself.

Baptist did present estimates of the

value of slaves as a percentage of total wealth. Olmstead and Rhode have

criticized these estimates. They point out that the estimates suffer from the inaccurate

citations that are typical of Baptist’s work and suggest that the slaves

accounted for about 14.1 percent of wealth not the 1/5th that Baptist

suggested. Baptist’s wealth estimates Table 7.1, however, are not outrageous in the way his

claim about production is.

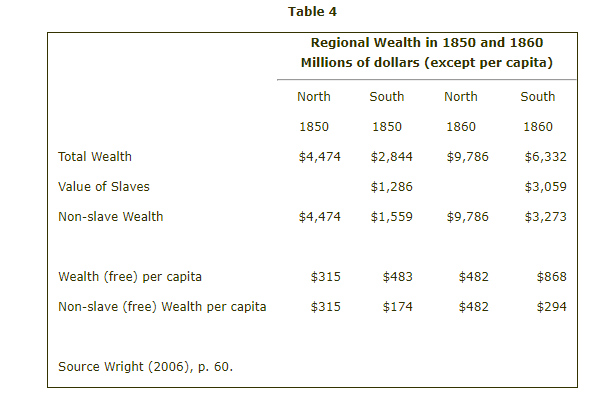

In fact they are pretty much the same as the

estimates presented in Table 4 from Measuring Slavery in 2016 Dollars by Samuel H. Williamson and Louis P.

Cain (based upon work by Gavin Wright). The value of slaves equaled about 18%

of total wealth. The majority of wealth was in the North, not the South, and slaves

did not account for the majority of wealth even in the South. Coates stated

about wealth was probably based on the frequently stated claim that the value

of slaves exceeded the value of railroads and factories. That claim is true,

but it is misleading because the United States was still primarily and agricultural

economy. A relatively small portion of wealth was in manufacturing and

railroads.

Coates history was accurate in

emphasizing that the story did not end with the end of slavery. It is bad enough

to deprive generations of people of the opportunity to create and pass on their

wealth, but the descendants of slaves were systematically, murdered, robbed,

and deprived of basic civil rights. I live in Fredericksburg, Virginia; I am 56

years old, and segregated schools here only ended during my lifetime. It was 1968 before an African American, Venus R. Jones, graduated from the public college that I teach at. Numerous

studies continue to document that African Americans are discriminated

against in courts, by bankruptcy

attorneys, by employers,

etc. The past keeps breathin'.

Finally, I will note that economists,

especially economic historians have been working on estimates of the value of

reparations for quite a while. The overall, approach tends to be similar to the

role that economists sometimes play in legal cases estimating the extent of

damages. The focus is usually on lost wages. If you are thinking that is a

relatively limited view of the cost of being enslaved, well, yes. In any case,

here is a recent

paper by the political scientist Thomas Craemer that refers to some of the

earlier literature, describes the difficulties associated with estimating the

loss to African Americans during slavery, and estimates how those losses should

be valued now.

My current inclination would lean

more toward focusing on the current disparities in wealth, which can be though

of as summing the effects of slavery and its aftermath.