Antebellum Economic Growth

Last week on Twitter Matt Yglesias raised a question about changes in how historians interpreted slavery. One historian, Joshua Rothman replied and Edward Baptist added his two cents.

I'm not sure what Rothman means by "in fact and as a matter of history." Perhaps it is reference to Baptist, who prefers to avoid mixing facts with his history. In any case, Rothman seems to believe that the centrality of slavery to American economic development is not something a reasonable person could dispute. I regard myself as a reasonable person. So, on the off chance that someone might be interested in why I would dispute the claim that slavery was central to American economic development I'm going to ask that we take a closer look at the antebellum economy.

The argument against the centrality of slavery is based on two things: the assumption that Rothman is using the word central as it is defined in the dictionary and used by most people, and the available evidence on the antebellum economy. Central means that something is not just important but that it is of primary importance. The central character in a movie is not just an important character, she is the main character, the primary character. This is clearly what Baptist has in mind when he claims that

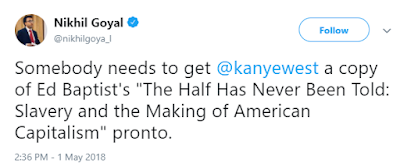

“the returns from the cotton monopoly powered the modernization of the rest of the American economy” and that "more than $600 million, or almost half of the economic activity in the United States in 1836, derived directly or indirectly from cotton produced by the million odd slaves― 6 percent of the total US population―who in that year toiled in labor camps on slavery’s frontier.” By the way, Baptist's tweet about it being easier to make claims about alternate universes than to come to grips with the past of this one was particularly appropriate given his expertise in making false claims. I and others have shown that Baptist's estimate is nothing but smoke and mirrors, a combination of numbers he makes up and bad accounting; see also Pseudoerasmus posts on Baptist. In addition, Olmstead and Rhode also show that Baptist made up things that he claimed to have found in the testimonies of enslaved people.

By the way, if Rothman actually just means to say that slavery was important, I wish he would do that. I don't know anyone who disagrees with that. When, however, he claims that slavery was central to American economic development he is helping Ed Baptist to keep pedaling his snake oil.

To show why I believe that it is not accurate to state that slavery was central to American economic development I begin by reviewing the growth of total output, then I look at the composition of this output, and then I look at the regional distribution of income generated from this production. I argue that the fundamental problems with Rothman's claim are that no one thing was central, and claiming that "one big thing" was central gives a misleading view of economic development.

I should note that the argument is not new. It is essentially the same approach that has been used to counter exaggerated arguments about the role of cotton textiles in the industrial revolution (see McCloskey by way of

Pseudoerasmus or the role of railroads in American economic development (see Fogel, but if you want the quick version McCloskey has a back of the envelope calculation of the impact of railroads in

The Rhetoric of Economics). I've made essentially the same argument

before. I'm hoping that by providing more detail about the antebellum economy that I might clarify the argument, make it more persuasive, and illustrate why most economic historians don't like "one big thing" theories of economic development.

I.

Overview

of Antebellum Economic Growth

Between 1790 and 1860 real GDP grew at a 4.4 percent annual rate, somewhat faster than the long run rate of growth (1790- 2000) of 3.87 percent. However, because population growth was also more rapid than the long run average, per capita real GDP increased at an average annual rate of 1.34 percent, somewhat less than the long run rate of growth of 1.77 percent (all growth rates are from measuringworth.com).

Real GDP in millions of 1996

dollars

Source: Historical Statistics Millennial Edition, Series Ca

9

Real GDP per capita

Source: Historical

Statistics of the United States Millennial Edition, Series Ca 11

Keep in mind we are

always talking about estimates. Nevertheless, these are estimates; not just guesses.

They are not simply made up numbers. If you want stuff that is just made up rather than based on actual historical research I suggest Ed Baptist’s work. Given these cautions we can look in more

detail at antebellum growth, but it is important to keep in mind that when I

say something accounted for about 3.9 percent of output in 1850, you should not ignore the about.

II. What Were People Producing?

What were Americans producing in the antebellum period? The table below shows how output was divided between

commodities and services. Over the course of the nineteenth century the share

of output accounted for by services was increasing, but commodities still

accounted for nearly 60 percent of output on the eve of the Civil War.

The next table shows the division of commodity output

between different sectors. Over the course of the nineteenth century the relative importance of manufacturing was increasing, but in the decade

preceding the Civil War agriculture still accounted for the majority of commodity output.

Source: Gallman, Robert E.

"Commodity Output,

1839-1899." In

Trends in the American economy in the

nineteenth century, pp. 13-72. Princeton University Press, 1960.

The following table shows how agricultural output was divided between livestock and crops. Unlike the previous tables, these tables show the value of output

rather than the share of output. It is, however, apparent that agricultural

production was split relatively evenly between crops and livestock.

The next table also shows the value of output and provides a more detailed breakdown of agricultural production.

On the eve of the Civil War, grain production was the largest source of income from crop production, but the most important single commodity was clearly cotton. Taken as a whole, however, the preceding tables illustrate why it is probably not useful to regard cotton, or any other single good, as the central to American economic development. On the eve of the Civil War, cotton

accounted for about 35 percent of the value of crops produced. That is a large

percentage, but because crop production was only about 51 percent of

agricultural output, cotton only accounted for about 17.8 percent (.35 x .51 =

.178) of agricultural production. That is still a large percentage, but if we

are interested in cotton’s importance for the whole economy, we must keep

going. Because agriculture accounted for 56 percent of commodity output in 1859

and cotton accounted for 17.8 percent of agricultural output, cotton accounted

for about 9.9 (.178 x .56 = .099) percent of commodity output. Finally, because

commodity output accounted for 59 percent of all output, cotton would have

accounted for about 5.8 percent (.099 x .59 = .058) of all output. If you

conduct the same exercise for 1850 you would get an estimate of about 4.8

percent. If you compare the cotton values from the above table with estimates of nominal GDP from measuringworth.com, cotton equals 4.95 percent of GDP in 1860 and 4.57 in 1850. Although the second method is more direct, I wanted to show why cotton is a relatively small share of the whole economy: people produced many different things. Even after cotton’s rapid expansion during the first sixty years of the

nineteenth century, it accounted for less than 6 percent of GDP.

I do not have as much information for manufacturing, but Joseph

Davis research on industrial production gives us some idea of the growth of

industrial output and the relative importance of different components of

industrial production. Below is a table showing the weights that he used for

different components of his index of industrial production, reflecting their

relative importance.

Source: Historical

Statistics Millennial Edition, Series Ca19

Employing the same sort of exercise as above, we find that cotton

textiles, the largest component in manufacturing in the United States would

have accounted for around 3.9 percent (.218 x.30 x .60 = .039) of GDP.

Livestock

production accounted for 15.5 percent of output. Food grain production

accounted for 3.7 percent. Total grain production accounted for 6.7 percent.

Let me reiterate my use of the word about. All of these are estimates, and the further back in

time we go the more the estimates tend to be based on smaller amounts of

evidence. It is all possible that I made an error in here somewhere. New estimates, however, are unlikely to change the overall conclusion

because cotton was only a fraction of all crops, crops were only a fraction of

all agricultural production, agricultural production was only a fraction of all

commodity production, and commodity production was only a fraction of all

output. Multiplying fractions tends to generate small fractions relatively

quickly. The math just reflects the underlying reality: the United States in

the early nineteenth century already produced a wide array of goods and services.

III. Where Were People Producing?

One could argue that the focus on cotton does not give an accurate estimate of the impact of slavery. Not all cotton was produced by slaves and slaves produced other things. However, a look at the regional distribution of income also does not support the primacy of slavery in economic development.

Regional variations in personal income reinforce the argument

that it is probably not useful to regard slavery and the cotton that enslaved people produced as central to American economic development. The following table shows estimates of personal income

generated in different parts of the country.

The North’s leading role in the economy was a consequence of

both more people and higher per capita output.

Source: Lindert, Peter H., and Jeffrey G. Williamson.

American

Incomes 1774-1860. No. w18396. National Bureau of Economic Research,

2012.

There is one final argument about the centrality of slavery that I should address. Some people claim that because of the spillover effects of slavery. This for instance is the idea behind Baptist's attempt to add up imaginary estimates to calculate the importance of cotton. There are two problems with this approach. First, you can do it with any good. For wheat I could count land sales, and the cost of transportation, and the cost of equipment, etc. Using Baptistian income accounting I could easily show that the amount of national output accounted for by grains and cotton was greater than the total output. How is that for an alternate universe? The other problem is that the evidence does not support the claims of strong interregional linkages during the antebellum period (see, for instance,

this post).

Conclusion

Slavery was not central to American economic development in the sense that it did not power the modernization of the rest of the economy. The claim that slavery was central to American economic development is factually incorrect: slavery was important, but no one thing was central. The claim also promotes a misleading view of the process of economic growth. It suggests that economic growth is about one big thing. No one thing was big enough to drive economic growth, not railroads, not cotton, not cotton textiles. Explanations for economic development need to explain why people were investing and innovating in a lot of different things. Consequently, economic historians have tended to move away from one big thing theories of economic growth toward understanding the underlying causes of development, such as the emergence of a culture of growth (

Mokyr), or the rise of bourgeois values (

McCloskey) or the evolution of growth promoting institutions (

North, Wallis and Weingast).

Slavery was not central to American economic development, but it was an important part of American economic development, and economic historians have devoted considerable attention to understanding slavery its continued impact on the American economy (see, of course, work by Fogel, and Wright, and for a small sample of recent work you can look at Logan, Cook, and Parman, Logan and Pritchett, Nunn, Naidu, and Collins and Wanamaker.