I think most people have a very vague notion of what the Industrial

Revolution was, and descriptions and pictures are not particularly helpful. You

really need to see a spinning wheel, a spinning jenny, and a water frame at

work to appreciate what was happening in the 1700s. I have been fortunate enough

to visit some great museums and see some of these things at work, but I don’t

have the opportunity to do that with my students. That is where Industrial Revelations

comes in handy. There are several seasons of Industrial Revelations, and I

haven’t had time to watch them all, but the first season with Mark Williams (aka

Arthur Weasley) is great for showing many important technological changes

during the Industrial Revolution. Here is a link to the textile episode,

which I think is one of the best.

This is a blog about economics, history, law and other things that interest me.

Monday, May 14, 2018

Thursday, May 3, 2018

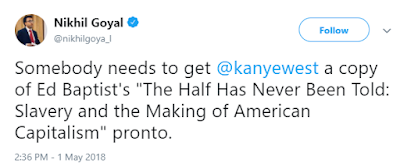

Stop Telling Kanye to Read Ed Baptist

Since Kanye West decided that the World had spent enough time

paying attention to people that are not him, I have seen a number of suggestions

for Kanye’s education. More than a few have been along these lines

If he were to read Baptist, Kanye, like many of

Baptist’s other readers, could learn all sorts of things that are not

true. He could learn that

1.

Before Ed Baptist, economists and historians did

not believe that slave owners were profit seeking capitalists. Many

historians and almost all economic historians viewed slavery as a profit

seeking enterprise.

2.

Slave produced cotton accounted for more than

60% of GDP. Baptist

made up numbers and summed them in an approach to national income accounting

that defies all logic.

3.

The pushing system was a term that enslaved

people used. Ed

Baptist made up the term (see section 4.1; on second thought, just read the

whole thing).

4.

Economic historians don’t think slave owners

used violence to coerce enslaved people. This

is simply not true.

5.

Baptist shows that innovations in violence led

to innovations in picking that drove increases in productivity during the

antebellum period. He never provides any

evidence to support one of the central claims of his book. See

the link for the previous point and this by

Pseudoerasmus, and this by Olmstead

and Rhode. I should also mention Trevor

Burnard as one of the first historians to call out Baptist.

If we want Kanye to understand the brutality of slavery, how

about Charles Ball,

or Solomon Northup,

or Harriet Jacobs?

If you think he needs to read some professor, how about Daina

Ramey Berry? Maybe if Kanye gets through these readings we can come up with

some more, but let’s not contribute to the miseducation of Kanye West by

telling him to read Ed Baptist’s terrible book.

P.S. Stop telling anyone to read Ed Baptist!

Wednesday, May 2, 2018

Thoughts on Kochs and GMU

1.

Cabrera sounds like Captain Renault. He should

have actually said that he was “shocked – shocked to find that there were deals

like this”

2.

The deals seem pretty stupid in terms of the

level of involvement that the Koch’s wanted. I say stupid because they should

have known that it would look bad when it came out, and it wasn’t necessary. As

long as the president and provost want the money to keep coming in they will

make sure the donor is happy.

3.

Provosts and presidents can do that because universities

are like schoolyards.

5.

I will continue to judge academics at George

Mason, whether they are in economics, Mercatus, the law school, or any other

department or center, based upon what they do as individuals. That means that Mark

Koyama and Noel Johnson are among the best economic historians

working now, Robin

Hanson and Arnold

Kling are willing to play fast and loose with evidence to support their

claims, and I still don’t understand why Tyler Cowen gets so much attention.

6.

This is the third time I have posted something

critical of Democracy in Chains and I still haven’t gotten any Koch money.

Monday, April 16, 2018

Diane Lindstrom (1944-2018)

At the risk of making this seem like a blog of economic

history obituaries, I think it is necessary to note the passing of Diane

Lindstrom. Here is the obituary

from the University of Wisconsin.

Along with Robert Gallman, Lawrence Herbst, Paul Uselding

and others Lindstrom challenged the version of American antebellum growth

presented in Doug North’s Economic Growth

of the United States, 1790-1860. In Economic

Growth Doug argued that growth was driven by a combination of cotton exports

and interregional trade, in which Southern specialization in cotton generated

demand for the products of farmers and manufacturers, driving growth in the

rest of the country. Although some new historians of capitalism continue to

cite the theory to demonstrate the central role of slavery in American economic

development, Lindstrom and others had built a strong case against it by the mid-1970s.

She generated evidence to argue that the South was largely

self-sufficient in grain:

Lindstrom, Diane. "Southern Dependence upon

Interregional Grain Supplies: A Review of the Trade Flows,

1840-1860." Agricultural History 44, no. 1 (1970):

101-113.

And she went on to build an alternative explanation of growth

based on the case of Philadelphia. She showed that the development in Philadelphia

was largely driven by the regional market, rather than an inter-regional one:

Lindstrom, Diane L. "Demand, Markets, and Eastern

Economic Development: Philadelphia, 1815-1840." Journal of

Economic History (1975): 271-273; Lindstrom, Diane. Economic

Development in the Philadelphia Region, 1810-1850. Columbia University

Press, 1978; and Lindstrom, Diane. "American economic growth before 1840:

New evidence and new directions." The Journal of Economic History 39,

no. 1 (1979): 289-301.

Subsequent economic historians have expanded on her work. John Majewski, for instance, builds on Lindstrom’s argument

by contrasting the case of Philadelphia with Virginia, showing how slavery led

to conditions that did not promote strong local demand or support long term

growth: A house dividing: Economic development in Pennsylvania and Virginia

before the Civil War. Cambridge University Press, 2000.

I did not know her personally, but anyone interested in understanding American economic development needs to know the argument she developed and the evidence that she collected to support it.

By the way, if anyone is surprised that I, a student of Doug’s,

am posting this you should know that the third edition of North’s Growth and Welfare in the American Past

(coauthored with Terry Anderson and Peter Hill) states that “The spread of the

cotton economy in the South and the development of the cotton export trade are

elements of a well known story. It now appears, however, that economic historians

have overemphasized the pattern of regional interdependence among the South,

the West, and the Northeast (page 72)” and cites Lindstrom in the bibliography

for that chapter. Doug once told me that the only good thing about getting old

was that he knew lots of things that did not work.

Tuesday, April 10, 2018

John Murray

Sad news. John was both an excellent economic historian and a really nice guy. Below is the text of the email about his death from EH.net. He will be missed by many people and in many ways.

John Murray, Joseph R. Hyde III Professor of Political Economy and Professor of Economics at Rhodes College, passed away on March 27, 2018 in Memphis, TN at the age of 58.

He was born on April 9, 1959 in Cincinnati, and became the first member of his family to attend college. He worked at a variety of jobs to pay his tuition, including phlebotomist, house painter, roofer, and ice cream vendor, graduating in 1981 from Oberlin College with a degree in economics. He later added an M.S. in mathematics from the University of Cincinnati, and the M.A. and Ph.D. in economics from The Ohio State University, where he wrote his dissertation under the tutelage of Rick Steckel.

John taught high school math before pursuing his graduate work in economics. After finishing at Ohio State, he accepted a position at the University of Toledo, where he remained for 18 years before accepting the Hyde Professorship at Rhodes College in 2011.

He had a lifelong penchant for learning, spending a summer studying the German language in Schwabish Hall in 1984, and summers as an NEH scholar in Munich in 1995 and at Duke in 2013. He also spent 2009-10 studying Catholic theology and philosophy at the Sacred Heart Major Seminary in Detroit.

Murray was the author of two books and co-editor of a third. The most recent, The Charleston Orphan House: Children’s Lives in the First Public Orphanage in America, published by the University of Chicago Press in 2013, was the recipient of the George C. Rogers, Jr. Prize, awarded by the South Carolina Historical Society for the best book on South Carolina history. His first book, Origins of American Health Insurance: A History of Industrial Sickness Funds (Yale University Press, 2007) was named one of ten “Noteworthy Books in Industrial Relations and Labor Economics” in 2008 by the Industrial Relations Section, Princeton University.

He published book chapters, monographs, encyclopedia and handbook contributions, and numerous articles in refereed journals including the Journal of Economic History, Explorations in Economic History, and Demography. His clear, crisp writing style and ability to explain complicated economic concepts made him a frequent choice to write for the popular press as well.

His research interests were varied. His most recent work centered on coal mine safety, post bellum African-American labor supply, and families in 19th century Charleston. He published extensively in the areas of the history of healthcare and health insurance, religion, and family related issues from education to orphanages, fertility, and marriage, not to mention his work in anthropometrics, labor markets, and literacy.

He was a scholar and a teacher, who believed deeply in the value of a liberal arts education, arguing that “a rigorous education, based on the traditional great books, teaches students great things—compassion for others in the human condition, the value of striving for greatness, the need for self-awareness, and humility in those efforts.” He won awards for his teaching at Ohio State and Toledo.

He was the director of the Program in Political Economy, a rigorous interdisciplinary major at Rhodes College. He taught a variety of economic history courses, including courses on demography and economic development, as well as mathematical economics, freshman calculus, introductory statistics, and econometrics. Then on the weekend he donated his time to his local parish, teaching Sunday School.

He was also generous with his time on a professional level, frequently reviewing books, and serving as the Book Review editor for the Journal of Economic History from 2014-16. He was a member of the editorial board of four journals: Explorations in Economic History (2008-15), the History of Education Quarterly(2016-19), Social Science History (1996-98 and 2006-14), and theJournal of Economic History since 2015. He served as the Associate Editor of Social Science History from 2001 to 2006.

He was a trustee for the Cliometric Society and served on its Program Committees, and was active in the Social Science History Association, holding numerous positions. He also served on numerous university committees at both Rhodes College and the University of Toledo.

More than a respected academic and award-winning author, John was a devoted husband and proud father. As impressive as his professional accomplishments were, his career always came second to his family. Conversations with John would eventually lead to family, and hearing him talk about them left no doubt about his true passion.

John is survived by his wife Lynn and their twin daughters.

Sunday, March 25, 2018

The Annunciation by Henry Ossawa Tanner

If you are in Philadelphia you should go see it at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Reproductions do not do it justice.

Monday, March 5, 2018

Quick Take on The Mystery of the Kibbutz

While the power was out this weekend, and I was free from

electronic distractions, I had a chance to read Ran Abramitzky’s The Mystery of the Kibbutz: Egalitarian

Principles in a Capitalist World. The book is a sort of economic history equivalent of good micro-history, or

good business history. It tells a particular story in great detail but uses that

story to shed light on broader issues. Being an economist, Abramitzky collects

and analyses as much data on the kibbutzim (one of the things I learned is the

plural of kibbutz) as he can to examine problems of free riding, adverse

selection, and brain drain. But the book is built around a very personal story.

His grandparents helped to found and fought to protect Kibbutz Negba; his

mother grew up there, and he clearly has fond memories of visiting there while

he was growing up. His aunt, uncle and brother still live in kibbutzim. He uses

the story of the origins, successes, and recent struggles of this and other

kibbutzim to address broad questions of equity versus efficiency, and of

material versus non-material incentives. There is also an interesting chapter

on the history of communes in the United States.

The book is a pleasure to read. And, although kibbutzim are

unique, the economic issues that they have faced are not.

Tuesday, February 27, 2018

What Happened to The Standard of Living During the Gilded Age?

Richard White devotes a chapter of his new book on

Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, The

Republic for Which It Stands, to declining standards of living during the

Gilded Age.

White writes that

“By the most basic

standards—life span, infant death rate and bodily stature, which reflected childhood

health and nutrition—American life grew worse over the course of the nineteenth

century. Although economists have insisted that real wages were rising during

most of the Gilded Age, a people who celebrated their progress were, fact, going

backwards—growing shorter and dying earlier—until the 1890s.” (page 475)

“The average life

expectancy of a white man dropped from the 1790s until the last decade of the nineteenth

century. A slight uptick at midcentury proved fleeting, nor was it certain that

the smaller rise in 1890 would be permanent.” “What this added up to was that

an average white ten-year-old American boy in 1880, born at the beginning of

the Gilded Age and living through it, could expect to die at age forty-eight.

His height would be 5 feet, 5 inches. He would be shorter and have a briefer

life than his Revolutionary forebears.” “Infant mortality worsened in many

cities after 1880.” (page 479)

White also notes the difficulty of creating historical

statistics but suggests that

“When these

statistics all point in a similar direction, they are worth of some attention.”

In general, White bases his interpretation on excellent work

done by economic historians. I do, however, want to argue that there is less consensus

than he seems to suggest. In other words, the statistics do not all point in a similar

direction when it comes to the Gilded Age.

I also want to point out there is a miscalculation in the statement

about height. White relies on Costa (2015) for the evidence on height; he includes

a version of the graph from Costa (see below) in which one can see that the

series hits its lowest point in 1890 at 169.1 cm, which translates to 5 feet

six and a half inches. I am sure that I would make many more grievous errors in

a 940 page book, but I had already seen the number repeated once as if it were

fact.

Nevertheless, the overall picture that White presents of material

well being during the Gilded Age is consistent with picture in the graph. Clearly

the most noteworthy feature of the graph is the decrease in average height and

life expectancy during the nineteenth century. The average height and life

expectancy fell relative to colonial ancestors before beginning to rise again

in the late nineteenth century. The timing of the movements in the series seem

to be consistent with each other.

Source: Costa, Dora L. "Health and

the Economy in the United States from 1750 to the Present." Journal

of economic literature 53, no. 3 (2015): 503-70.

I want to argue that the evidence of declining living

standards in the Gilded Age is not as consistent as White suggests. Estimating life expectancy in

the United States during the nineteenth century is extremely difficult and different

approaches have produced different estimates. They all suggest that life

expectancy fell during the nineteenth century, but they do not all estimate

that life expectancy reached its lowest point in the late, as opposed to the

mid, nineteenth century. Estimating average

heights is also difficult, and recent work suggests that the series reproduced

by White may overestimate the extent of the decline and place the low point too

late in the nineteenth century.

The United States did not have a death

registry for the entire country until 1933. Some states and localities

registered deaths, but we are left with questions about how representative they

are. One innovative approach to the problem has been to use genealogical

records (see Fogel 1986). Beginning in 1850 the Census began to ask

about people that had died in the last year, which can then be used to

calculate life expectancy. On the numerous shortcomings of both types of data

see Hacker (2010).

Source: Hacker 2010

The above figure is from Hacker 2010 and presents four

different series of estimates of life expectancy at age 20. Only the Haines

series based on census data shows in the late nineteenth century. Both the Pope

and Kunze series bottom out in the 1860s.

Source: Hacker 2010

The mortality rates for several large cities also do not

seem consistent with worsening conditions during the Gilded Age. There is a

reduced incidence of large spikes in mortality, though there also isn’t a clear

trend toward declining mortality rates until late in the 19th

century (See Haines 2001).

The nineteenth century height estimates are based, for the

most part, upon a large sample of Union Army soldiers. I say for the most part

because late nineteenth century estimates are based upon an extrapolation from

Ohio National Guard data. The figure below from Costa and Steckel shows the

part of the series that is inferred from the Ohio National Guard data.

Source: Costa and Steckel, Long Term Trends in Health,

Welfare, and Economic Growth in the United States

Economic historians have long recognized that there are potential

problems with these estimates. The problem is not just that they might be

biased, but that the bias might change over time. On the other hand, if shorter

than average people became more likely to join the army or the national guard

then our estimates might suggest a decrease in average heights that did not

occur.

Although the potential for selection bias was known, later

research found similar patterns for the antebellum period in a variety of other

populations, for instance Ohio prison inmates (Maloney and Carson 2008) and Pennsylvania

prison inmates (Carson 2008).

Bodenhorn,

Guinane and Mroz (2017) recently argued that sample selection bias is a significant

problem in the height data. Ariell Zimran

has attempted to match soldiers with their census records and use the

information to adjust for selection bias. He concluded that, after adjusting for

selection bias, there was still a decrease in average height of about .64

inches between 1832 and 1860.

Matthias Zehetmayer took a different approach. He developed

a more comprehensive sample of soldiers. Because his observation extended into

the late nineteenth century he did not have to rely on an extrapolation for the

years after the Civil War. The graph below compares Zehetmayers estimates with

previous estimates. His estimates follow the original until you get to

the extrapolation from the Ohio national guard. Zehetmayer finds increases in the 1870s and 1880s rather than a steep decline.

Source:

Zehetmayer 2011

There are a lot of evidence pointing to a decline in height,

but there is no consensus that about when that decline began to reverse or even

if it might be explained by selection bias. Zehetmayer's recent estimates do,

however, seem to be consistent with the life expectancy estimates of Pope,

Kunze, and Hacker, reaching a low point in the 1860s or 1870s rather than 1890.

I think White was right to emphasize the difficulties involved

in creating historical statistics. Like other interpretations of history our

knowledge of material well-being in the past has to be derived from the bits

and pieces that were left behind, even if they are not ideally suited to the

task. Although estimates are very consistent regarding a declining standard of

living in the ante-bellum period, they are much less consistent about a decline

during the Gilded Age. The most recent estimates of both height and life

expectancy seem toward rising standards of living during the late nineteenth

century.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)