I saw a celebration of Ayn Rand online the other day (her birthday was Feb. 2). So thought I would post this, though I don't think you can really describe it as being in honor of her birthday.

I don’t like really like Ayn Rand’s fiction. If I just

thought it was bad fiction, I would probably ignore it. I usually only criticize fiction when it is masquerading as history. But many people seem to

think that Rand’s fiction has important things to say about reality. One

of the central messages seems to be that progress depends on the efforts of a

few great people. In general, American’s seem to like “Great Man” theories of

business history. If you want to sell books write another big biography of J.P.

Morgan, Ford, Rockefeller, Vanderbilt, or Carnegie. Rand’s heroes are extreme

versions of the great man theory of business history. They tend to start with

nothing and struggle ceaselessly against both the government and all of

the ignorant, incompetent and just plain lazy people that surround them.

For instance

“Nathaniel Taggart had been a penniless adventurer who had

come from somewhere in New England and built a railroad across a continent, in

the days of the first steel rails.” “He never sought any loans, bonds,

subsidies, land grants or legislative favors from the government.” He never

talked about the public good.” “Taggart Transcontinental was one of the few

railroads that never went bankrupt and the only one whose controlling stock

remained in the hands of the founder’s descendants”

Or consider the story of Henry Reardon

Henry Reardon began working in the Minnesota iron mines when

he was 14 and had built a business empire by the time he was 30, struggling

constantly against the incompetence of those around him. Of the times that he

had worked for others, “All he remembered of those jobs was that the men around

him had never seemed to know what to do, while he had always known.” Even after

he was the boss, he remembered “the days when the young scientists of the small

staff that he had chosen to assist him waited for instructions like soldiers

ready for a hopeless battle, having exhausted their ingenuity, still willing,

but silent, with the unspoken sentence hanging in the air: “Mr Rearden, it

can’t be done—”

The problem is that these stories do not resemble the stories

of actual business history.

I have seen it suggested that Nathaniel Taggart was a thinly

veiled version of James J. Hill, the Empire Builder, who built the Great

Northern across the northern plains without any government grants or assistance.

Hill was a very successful railroad executive, but he did

not build the Great Northern without government assistance. First, as John Rea

noted years ago the Great Northern was built on the foundation of the failed St.

Paul and Pacific Railroad, which had received 3 million acres in land grants (Rae,

John B. "The Great Northern's Land Grant." The Journal of

Economic History 12, no. 2 (1952): 140-145). One might, of course,

argue that Hill and his partners did not directly receive the grants; they had

to pay for them when they purchased the bankrupt railroad (though it should be

noted that one of Hill’s partners was a lawyer who was also serving as the

trustee for the bondholders). So, let’s put those land grants aside.

The sort of subsidies that railroads like the Union Pacific

received in which they received large grants of land on each side of the road,

were generally not an option when Hill was building the Great Northern. In the 1870s,

the federal government had shifted away from providing land grant subsidies. But

that does not mean that the Great Northern did not receive any government land.

Any incorporated railroad could obtain access to public land for the

construction of a railroad and related structures like stations by using the

General Railroad Right of Way Act of 1875. We know that the Great Northern used

the Act because it went to court to contest the rights that had been granted

under the act (Great

Northern Ry. Co. v. Steinke and Great

Northern Ry. Co. v. United States.)

Unlike the land grant subsidies, the Right of Way Act did

not bestow special treatment on particular railroads. Consequently, it might be

viewed as another step toward an open access order, like general incorporation

and free banking laws. On the other hand, it does not seem reasonable to claim

that being allowed to build on public

land is nothing. The federal government had purchased the land in the Louisiana

Purchase, and the federal government had driven Native American on to

reservations to make way for railroads and settlers.

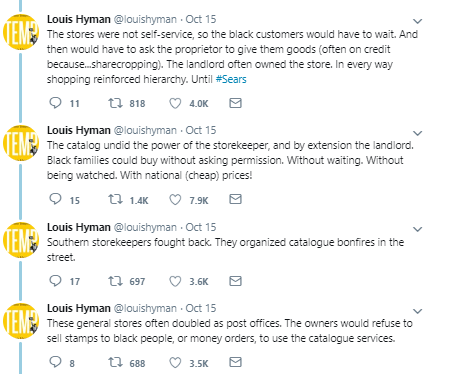

This is a map showing the general location of Native

American tribes in the mid 1800s

Minnesota, North Dakota, Montana, Idaho and Washington, were

not un-populated lands waiting for James J. Hill to build a railroad and promote

pioneer settlers. They first needed to be depopulated. This was done courtesy

of the United States government. These are the locations of Native American

reservations when Hill went to build his railroad.

It turns out, however, that even driving Native Americans on

to reservations was not enough for Hill, because one of the best routes

required going through a reservation. Hill appears to have been able to put

aside his aversion to the government to lobby to either have the size of the

reservation reduced or be given the right of way to build on the reservation (Smith,

Dennis J. "Procuring a right-of-way: James J. Hill and Indian reservations

1886-1888." (1983) see also White, W. Thomas. "A Gilded

Age Businessman in Politics: James J. Hill, the Northwest, and the American

Presidency, 1884-1912." Pacific Historical Review 57, no.

4 (1988): 439-456.

These are the reservations in 1888 (both maps are from Smith, "Procuring Right of Way")

Fans of Hill, like Burton Folsom see only Hill’s

business genius: “James J. Hill showed us the right way to build

infrastructure. He built slowly and chose the best routes. When Hill learned

that the best route west probably lay through the Marias Pass in Montana, he

was determined to build his railroad there. The explorers Lewis and Clark had

traveled through the Marias Pass and discussed it in their diaries. But in the

1880s, no one knew where it was. Hill’s chief engineer, John Frank Stevens,

trekked through the Rockies in Montana with a Blackfoot Indian guide named

Coonsah. The pair located the Marias Pass, and Hill used that shorter route to

save many miles of construction.” But we should remember that the crossing of

the Marias Pass was preceded by the Marias Massacre in which U.S troops killed

around 200 Blackfeet men, women and children.

In other words, Nathaniel Taggart and the Taggart

Transcontinental are fictions based on myth.

The self-made man, who not only receives no aid but must

constantly battle the weak and stupid people around him, is also not what

American business history looks like. Pamela Walker Laird’s Pull picks apart this myth, exploring

the many ways in which self-made men like Ben Franklin and Andrew Carnegie actually

benefited from the aid of others.

Henry Ford’s “invention of the automated assembly line”

depended on the work of Charles Sorensen, Walter Flanders, Clarence Avery, and

Ed Martin. Edison worked with the mathematician Francis Upton to develop his

version of a light bulb. Mc Donalds is the result of both the McDonald’s brothers’

vision of a fast food restaurant and Ray Kroc’s vision of how far it could be

taken.

The story of Ellis Wyatt, who “had discovered some way to

revive exhausted oil wells and he had proceeded to revive them” is illustrative.

In Rand’s imagination an entire region was revitalized and “One man had done

it, and he had done it in eight years.” The process of getting oil out of places that people had thought it impractical if not impossible sounds a lot like fracking. In

reality, many people played a role in developing fracking. In 2006, the Society

of Petroleum Engineers honored nine people as pioneers in the development

of fracking.

To be clear, I do believe that what Schumpeter referred to

as the creative response is central to economic growth and development. And I believe

that an open access society in which people are generally allowed to pursue these

creative actions is likely to be most conducive to human welfare. I am, after all, and economist. I like voluntary exchange in markets and I think people respond to incentives. I just don't believe in the sort of philosophy that regards whatever someone earns as "the fruits of their labor" as if the amount of fruit that you get in life doesn't depend crucially on the society your were born into and you place in it, things that have nothing to do with your labor. I don't see evidence that the creative response the creative response is the result of a select group of great

people struggling against the ignorant and ignoble masses who seek to hold them

back. My reading of history suggests that these creative people depend upon both the

help of others, their society, and an effective government.

But why should I be concerned about an inaccurate picture of

business history in a work of fiction? I'll just leave you with this quote. “Any refusal to recognize reality, for

any reason whatever, has disastrous consequences.”